Bluetooth for proximity detection

Crownstone is a company that has years of experience with indoor localization using Bluetooth Low Energy (Bluetooth LE). With the current spread of the Covid-19 disease, it is intended to roll out so-called contact tracing apps. Its aim is to collect knowledge about contact events. There is a time window in which the SARS-CoV-2 virus can transmit from one person to the other when they are in each other’s physical proximity. The proximity between two smartphones can be used as a proxy to the proximity of people. To the astute observer, yes, this does take into account neither surface contamination, nor the ability of a virus to remain floating in the air for longer times. It is an approximation of the risk of infection.

On personal title Anne has already describe a few of the challenges that the use of Bluetooth LE implies. At Crownstone, one of our core values is transparency. For that reason privacy is a very important right to us. However, we won’t touch that topic here. For starters, it is important that a technical solution works. Let us illustrate this with a short parable. If cameras would be deployed to recognize bike theft, but there are reasons to assume that the computer vision algorithms won’t work, it is important to listen to those “annoying techies”. If it does not work, it does not work…

Bluetooth LE

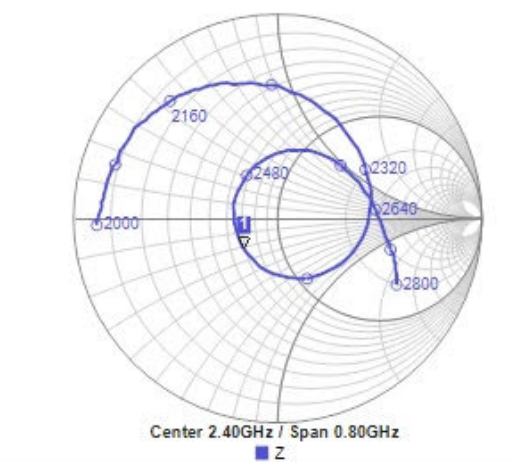

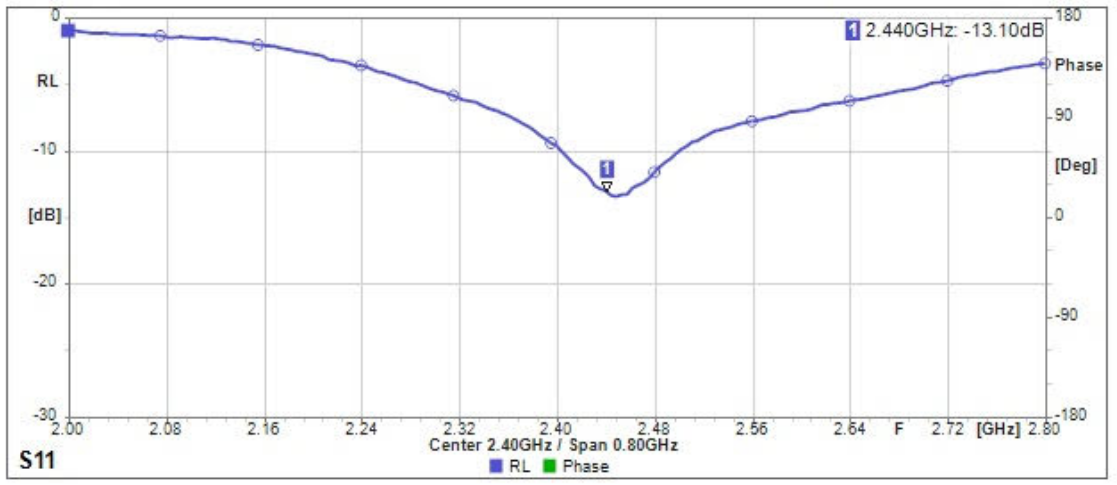

The Bluetooth LE packets are sent using a Bluetooth chipset and radio on your smartphone. On an iPhone or Android this can e.g. be the Broadcom BCM43xx family (read this story from a reverse engineer to learn much more). The radio broadcasts signals through an antenna. Those radio waves can be modelled by a program like that of Comsol. The performance is typically analyzed with a Smith chart (impedance), return loss diagram (bandwidth), and so on. Below you can see two figures at a state where we were still tuning the antenna together with the Van Mierlo engineers.

Orientation

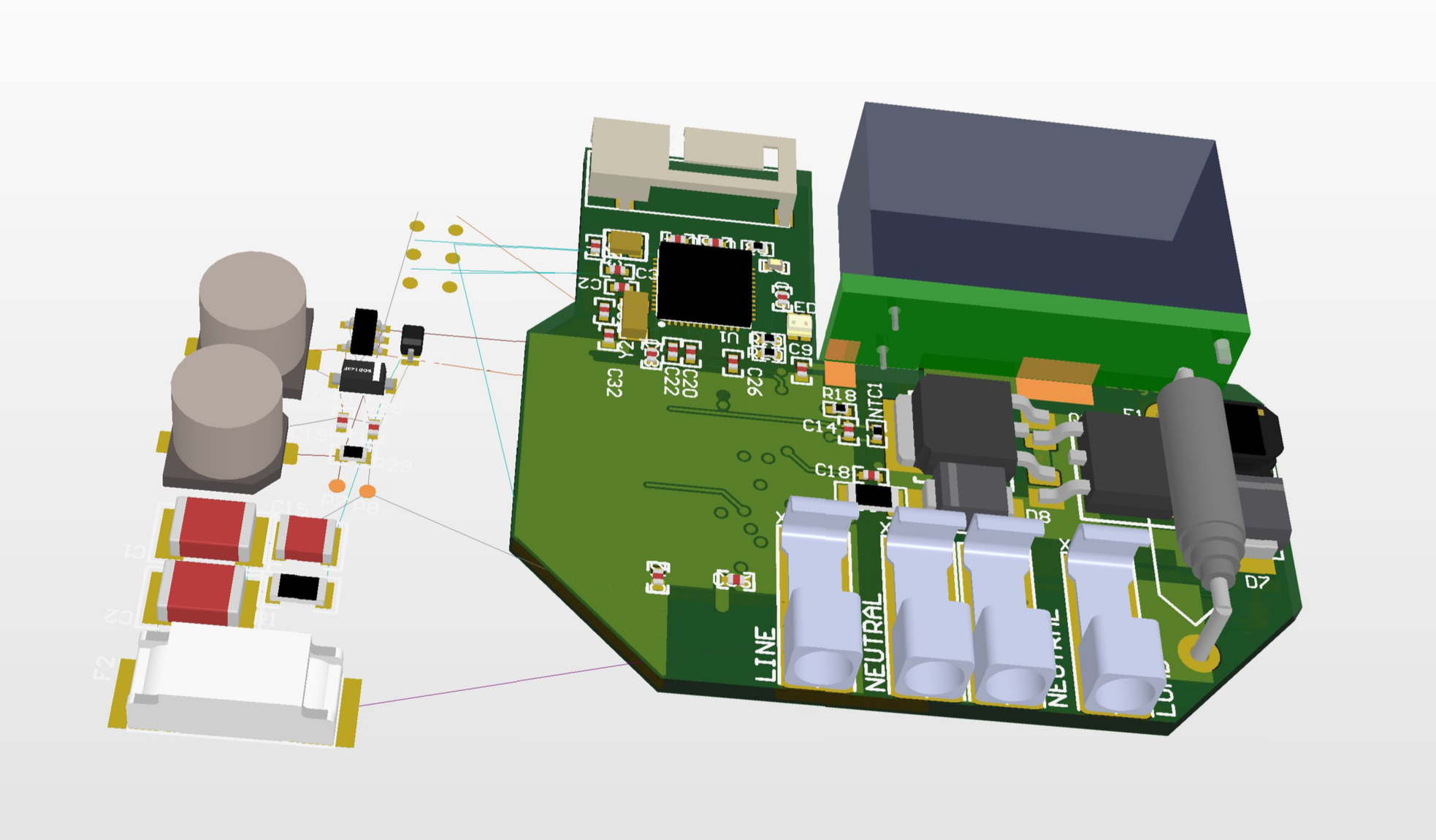

We decided in the end to use a different antenna. The details of this ProAnt OnBoard SMD 2400 Antenna (PRO-OB-440) can be found in the datasheet and application note.

You see how the orientation of the antenna has influence on the radiation pattern. This is very typical of antennas and they differ in how “spherical” the pattern is. You see that it’s even different for horizontal polarization (HP) versus vertical polarization (VP).

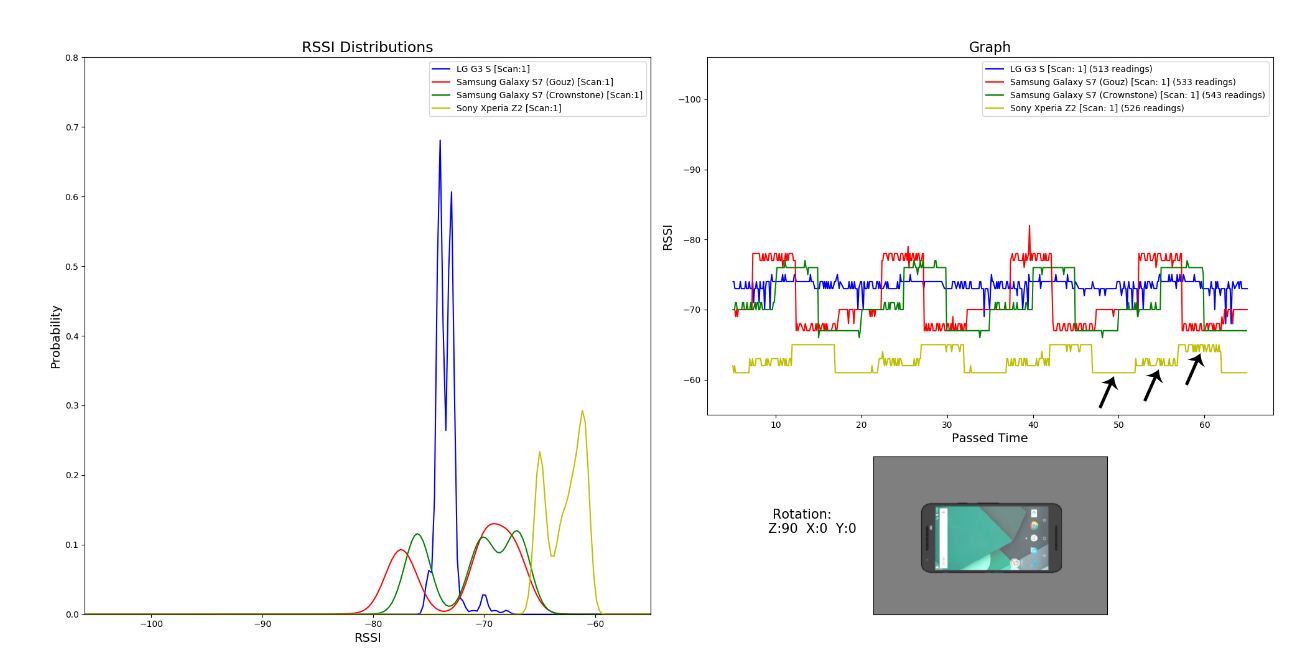

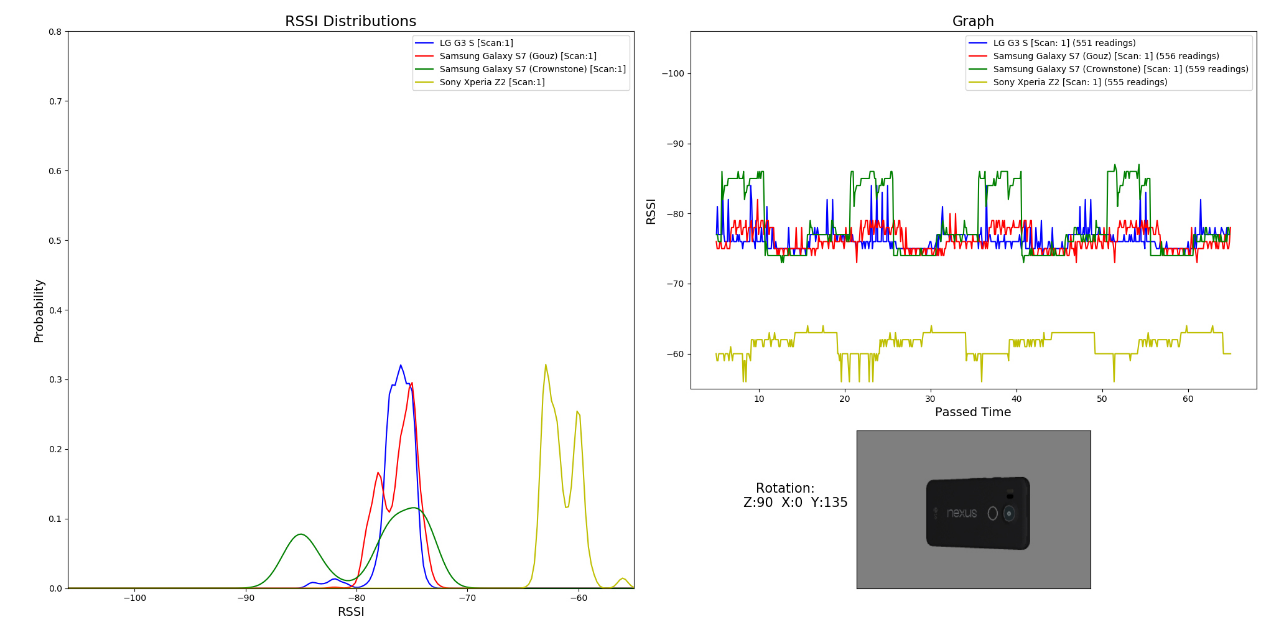

One of the interns at Crownstone studied these effects in detail. For example, here you see the antenna aspects of multiple phone models in an indirect manner, namely through the signal strength values with which the phones registers the strength of the incoming message.

Now we rotate the phone and we see completely different distributions.

The Bluetooth spectrum runs from 2402 MHz up to 2480 MHz and is divided into 40 channels. The channels used for the Bluetooth LE advertisers in these applications are 37, 38, and 39. To best cope with interference they are spread very widely, the first channel at the beginning, the second somewhere in the middle, and the third at the end of the spectrum. Each channel comes with different properties and that is very clearly visible in the pictures of above. Orientation has a lot of impact on the signal strengths per individual channel.

A potential benefit of Apple and Google writing their own code would be that they can make use of this information. That this will be done is very unlikely. Yes, the information can be used to improve distance estimates, but it takes considerable engineering effort to do this over all possible phone types, antenna configurations, and the presence of covers, headphones, or battery packs outside of a lab setting.

Obstructions and reflections

A radio signal does not only travel in a straight line. For OpenTrace, the reference implementation of BlueTrace, the protocol underlying the TraceTogether app from Singapore, there has been some good work on calibration (pdf).

It is not hard to imagine that messages from a smartphone in a pocket or handbag are received at lower signal strengths than if they do not have to penetrate to those materials. There are other aspects that are relevant to indoor situations and to moving objects. Indoors the signal can be reflected on surfaces. The combined signal at the receiver can sum up to be large due to those reflections. This multi-path attenuation will give results where it seems someone is closer than they actually are. Similarly, with particular phase difference, reflections subtract from the received signal power. When two people are walking phase shifts change continuously and have to be taken into account. In this article it states that the fading effects cannot be neglected, at least for moist ground when there’s ample reflection.

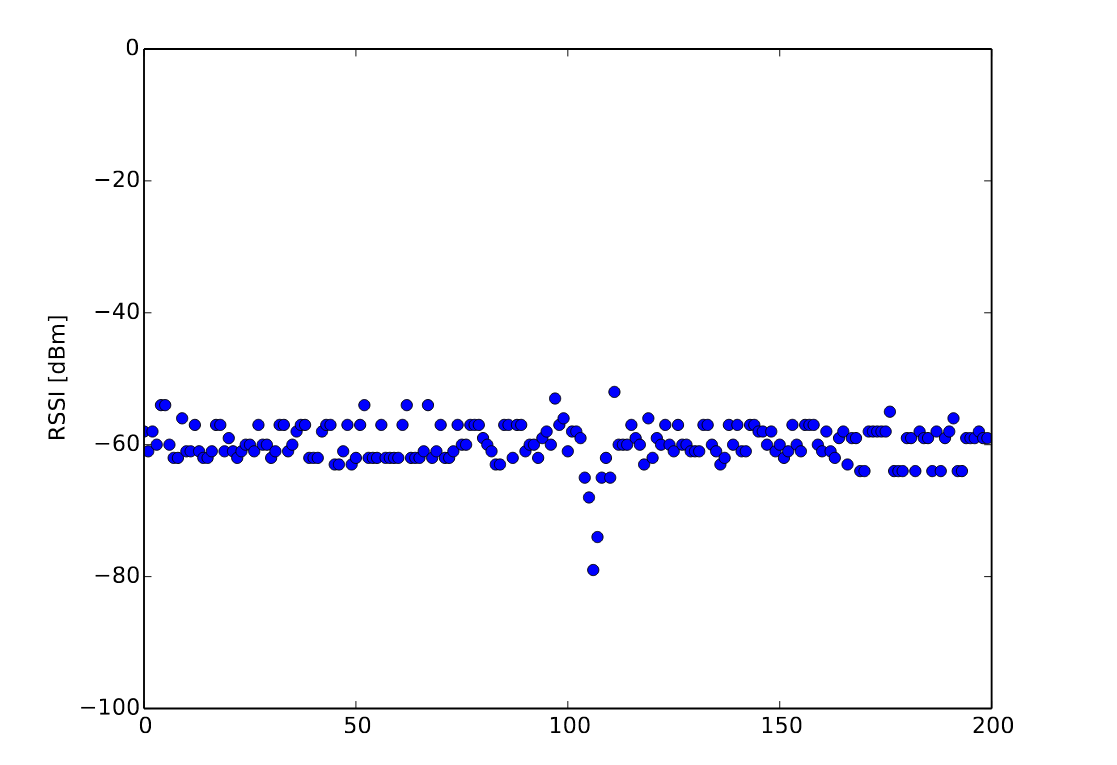

To understand the impact of people themselves, a study by another intern at Crownstone might be enlightening. We already knew that there were many aspects that were influencing received signal strengths. Hence, we thought how to make use of that, rather than see it as an enemy. The question rose: If we carefully monitor signal strengths, can we derive information on walls, doors, or people? The latter we called device-free localization.

In this graph a shadowing effect is shown. The received signal strengths are monitored between two Crownstones facing each other. A person walks through the “virtual beam” of communicating Bluetooth LE messages. You see a drop due to this shadowing effect. The signals do not pass through the person for a short period.

That shows how good our body is in being an impenetrable barrier for Bluetooth signals. If your phone is in front of your body, the signals received at your back will be much and much weaker than the ones in the front.

How then does Crownstone do it?

If this all is so hard, how come Crownstone’s system works? There are two reasons for this: (1) the use of multiple Crownstones, and (2) self-learning algorithms.

Use of multiple Crownstones

At Crownstone we can quite accurately pinpoint the location of a user, but for that we use the signal strengths of messages that arrive from multiple Crownstones. We combine those with algorithms to derive the location of a user. If you place the Crownstones very close together you can get extremely high accuracies. Bluetooth LE accuracy is therefore not just depending on the signals itself. If you have multiple of those signals you can learn much better if someone is nearby.

The above movie shows a demo where the position is estimated at a level of centimeters rather than meters. Note that this requires a high density of Crownstones. It is not practical in the real world!

Self-learning

Another aspect why the Crownstone system works, while contact tracing is much more difficult, is the fact that it is self-learning. The Crownstones - because every phone can be different - ask for the help of the user. The Crownstone’s AI on the phone asks the user to walk around in a casual way, e.g. with the phone in their pocket or in their hand. During this process it collects all signal strengths while the user stays in the same room. After this learning process, the system generates a fingerprint of the room. At a later stage, when a particular pattern of signals is seen, it is matched with the fingerprints and the classifier outputs the most reasonable guess for the current room.

A system like this won’t work for contact tracing. It can be done in the lab, with contact events simulated by people passing each other. However, this information is hard to obtain from the field, especially given privacy constraints.

Summary

There are many other technical and operational facets as well, as already described in this post. For example: the ability of Bluetooth LE signals to travel through walls, through ceilings, through glass. Another example: the difficulty of taking 3D into account. Imagine a flat with the upstairs neighbour only two or three meters away. Think of someone sitting on a balcony and someone walking by. There are also considerations with respect to the smartphones themselves from allowing processes to run Bluetooth in the background (one of our most popular technical posts). The TraceTogether app for example asks iPhone users to run the app in the foreground and upside down.

There are also tradeoffs between scanning, advertising, key rotation, and battery consumption. There are even questions of efficacy: contacts happen between two parties. Both have to have a system that works properly. If 60% of the people (that’s a lot!) install the app, we have only 0.6 times 0.6 = 36% of the potential contact events covered. If the app works for 80% of those people (questionable) this drops to the square of (0.6 * 0.8) = 23%. If the detection rate is 80% (questionable high as well) it drops even lower. Note that in the true world, there are false negatives besides false positives, which can strong demotivate people as well. If you get a warning that you were close to someone infected every day, it will not work.

There is very little reason to assume that this is the right technology for the job. There can be many ways in which technology helps in this crisis though. Let us all be creative and find those ways!

References

- Indoor Localization using BLE (pdf) by T. van Dijk. Faculty of Mechanical, Maritime and Materials Engineering (3mE)·Delft University of Technology.

- Translating BLE Received Signals across different Smartphones (pdf) by D. Xenakis. Geomatics for the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology.

- Contact Tracing Coronavirus COVID-19 - Calibration Method and Proximity Accuracy (pdf) by H.J. Meckelburg. Rurh-Univerität Bochum.

06 May 2020

Show Comments

(not shown automatically to support your privacy)